The house phone rang. I hesitated to answer it.

A voice on the other line introduced herself as my grandmother’s friend I had met a time or two.

“I hope I’m not bothering you.”

So began a conversation that joined us in pain and healing.

The call came a few weeks after the stillbirth of our longed for, prayed for daughter.

Our Story

Diagnosed with her Turner’s Syndrome and severe heart defect at our 20-week prenatal ultrasound, we proceeded with the pregnancy with the knowledge that the next flutter or kick might be the last felt; the heartburn would stop, the vague nausea and fatigue of pregnancy would cease, and we would go in for a tragic delivery. But one more week turned to two, and two more turned to a month, and hope emerged over the possibility that we might actually meet our baby despite having to say goodbye to her in a hospice birth setting.

We formulated two birth plans, one for each possibility, quiet strategies for how my husband and I might emerge from an unthinkable experience with a shred of ourselves intact.

Six weeks later, realizing she had died, arrangements were made for the delivery of our daughter we named Isabel.

Not strangers to loss, our desire to start a family was meeting hurdles, and Isabel was herself an answer to a prayer following an earlier miscarriage.

We departed Sacred Heart Hospital feeling loved and supported by the staff, buoyed by our families, and lifted up by our friend and priest who had baptized our tiny girl in the quiet hours of the night as we held her.

And knowing our God loved us, we loved one another, and we held on.

Friends and family with good intentions gave us space, but I floundered in the expanse of aloneness during the days and the heavy silence of the nights.

Until that call.

Her Story

She told me of her seemingly healthy pregnancy, but her early labor; she spoke of her husband, alone in the hospital waiting room when she went back for delivery, “how it was done in the 1950s.” She told me about the gas they gave her to relax, the deep sleep, and the vivid dreams of her baby boy.

But she awoke. There had been complications. He had passed, and they had taken him away.

She never saw her son.

Never held him through the night like we did our tiny girl. Never bathed him like my husband bathed our daughter. No chance to christen him, or wrap him in a hand sewn blanket she made as I had done.

It was a different time, she said. They had named him and buried him and mourned him, and they had gone on to have other children.

But she had missed much on that long ago night in the heavy ether fog; gaps in the story plagued her even still.

“Can I ask you some questions?”

She asked me about things we had otherwise been private about, details that she craved. So I shared. Understanding and relief filled her voice as pieces of my story slipped into place for hers, a 50-year-old puzzle a little closer to complete.

Her “thank you” was gentle punctuation on our final sentences.

Fifteen years later, my own family is complete, and this lady, living to a lovely age, has since joined her infant son in eternity.

But I remember.

Choosing to Remember

While life has, in fact, “gone on” for me, too, I choose to remember the details of the night. I replay its events in my mind with near-perfect recall of sounds and sequences, not because I’m trying to torture myself, but because I learned that remembering is a privilege.

I can remember the night that broke my heart, but not my soul; the night that clouded my future but did not occlude my hope.

The world today is more open to vulnerability made public and shared, recognizing that knowledge and remembrance contain healing powers.

Generations before mine didn’t share— much less post publicly— their stories of loss or pain, and surely there were plenty. But I’m not sure that was because they were stronger. In many cases, like this elderly friend, it was because they weren’t even given the chance to live their own story in that “different time.”

That phone call–the harbinger of other phone calls and conversations with other mothers–has repeated itself in various forms over the last fifteen years. Women–known to me or through my friends who needed someone to listen to their story– called, speaking details that felt safe in the comfort of shared experience. Others called, needing to know what to expect as their own tragedy loomed.

Out of that first call, an unintentional and informal ministry grew, and I realized how absolutely critical it was for the unspeakable to be said.

Fifteen Years

For me the details are still in place with near-perfect recall. Fifteen years now sounds like such a long time, and sometimes it feels silly to look back from my perfect picture into the times of painful loss, but my remembering is not seeded in wallowing.

The privilege of having my memories of that night provides me the joy of recognizing myself in “the after”– the woman who picked up the shred that remained of her that night, the wife who held onto the arm of her beloved, and the mother who was made even without a child to bring home.

Sometimes I see little Isabel in the haze of a beautiful dream, in the place between heavy sleep and real waking life. In my dream, I hold her, still small and pink faced, still wrapped in my hand sewn blanket.

I choose to remember because I can.

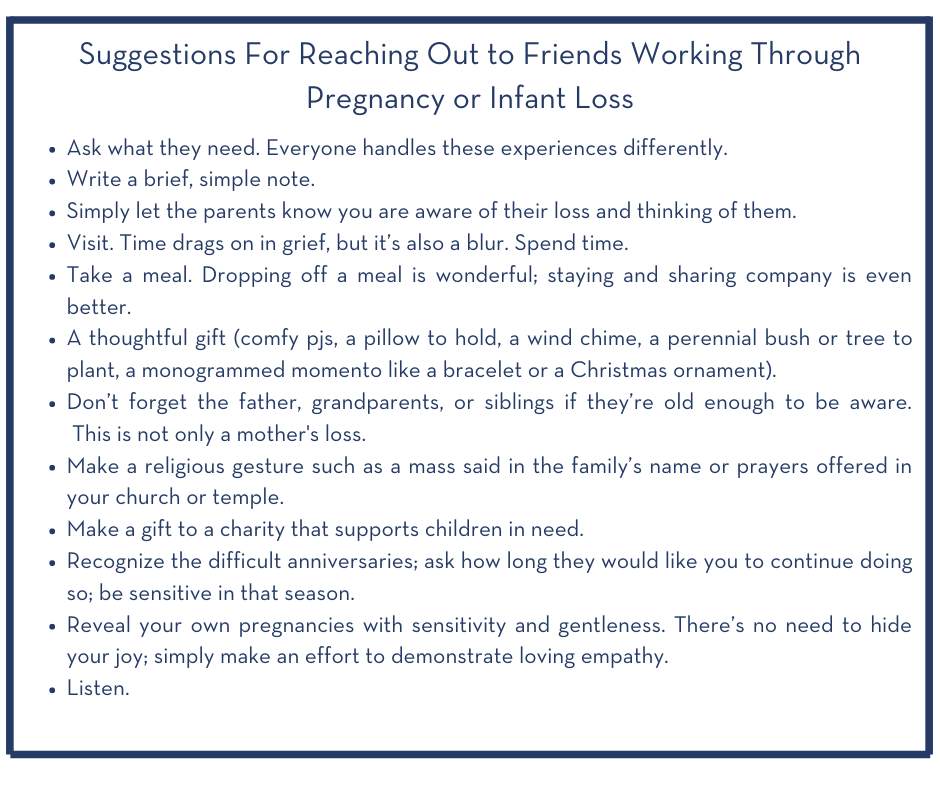

[…] rare and not something you could control. I share this in hopes that it offers the lens without the pained experience. And perhaps a reminder that you can spend your days worrying and doing all of the things up to […]

[…] abroad, graduate school, miscarriages and high-risk pregnancies, a layoff, starting a business, a parent’s illness, and death. Moves […]