We can all look back on a moment in our school years that had a deep and lasting impact on our lives. For me, it was the suggestion for my history fair project in the 8th grade. As it turns out, the woman who led the first unit of female military pilots in World War II and would later go on to be the first female pilot to break the sound barrier was born and raised just down the road in DeFuniak Springs. I had no idea why my teacher was so determined that I should research this particular topic, but I am eternally grateful that she was.

Women’s History Month wasn’t a huge thing at that point, and I had certainly never heard of Jacqueline Cochran or the Women’s Airforce Service Pilots in a textbook.

I reluctantly agreed and set off on a research project that turned into years of poring through old records, interviews, and trips to air shows around the country. More importantly, it introduced me to women who became friends and real-life heroes.

Here’s the quick story: in World War II, every available male pilot was needed for combat. Two women of drastically different backgrounds, Nancy Love and Jackie Cochran spent years working to convince the Army Airforce to try a training program for female pilots to fill domestic jobs. The agreement was reluctant at best. Trainees and graduates were not granted full military status or benefits, but that detail didn’t even occur to the 25,000 women who applied. They loved to fly and wanted to serve their country. The W.A.S.P. program ran for just over two years and graduated over a thousand women who flew every aircraft in the Army Airforce arsenal. They trained male pilots for combat, ferried aircraft, flew target practice missions, and tested new or repaired planes.

The female pilots proved their muster beyond question. Their safety statistics were actually better than the men’s, and at times the big brass would have female pilots fly their most dangerous planes to shame the men into getting into the cockpits.

Thirty-eight women lost their lives in the service of their country with no military benefits for their families or even transportation home for the bodies. When the program was disbanded in 1944 by a narrow vote in Congress, pilots who had filled a critical void were dismissed with a quick thanks and their memories to keep, but nothing more.

General Hap Arnold, the head of the AAF, addressed the last graduating class in 1944 validating how much they, and the rest of their unit, had accomplished:

“You, and more than nine hundred of your sisters, have shown that you can fly wingtip to wingtip with your brothers. If ever there was a doubt in anyone’s mind that women can become skillful pilots, the W.A.S.P. have dispelled that doubt.”

For thirty years, their story went largely untold and their service unrecognized. Finally, in the 1970s, the W.A.S.P.’s military service was recognized, and in 2009 the W.A.S.P. were awarded the Congressional Gold Medal.

As I interviewed some of the remaining pilots and learned more details of the program, I became more flabbergasted that these women were not even mentioned in our textbooks. They, on the other hand, were simply flattered that someone cared enough to ask.

The joy in their eyes anytime they spoke of flying among the clouds was contagious. I met ladies who had fudged their age, height, or number of flying hours just to have a chance to do what they loved while serving their country.

I came to count many of the women as friends. One, in particular, became like a grandmother to me. I relished my time with them, listening to flying stories sprinkled with life lessons, watching their eyes light up at the sight of an old warbird, and listening to them sing “Wild Blue Yonder” with more enthusiasm than a brand-new recruit.

Though their service was largely unknown – and thereby unappreciated – I never once heard any bitterness in their voices. I only heard words like “lucky” and phrases like “dream come true” when they described their time in the program. Even when they had just finished telling a story about an instructor hell-bent on failing every female he taught. These ladies had the last laugh. No instructor, rattlesnake in the cockpit, or broken-down plane could have held them back from earning those silver wings.

I learned what it looks like to accomplish incredible feats without concern to who got the credit, just that the job was done well.

The pride they exuded anytime they met a female pilot told you without a doubt that these women did their job well. They had played a part in making that pilot’s career a possibility, and her success was the greatest achievement of their lives.

In one conversation, I asked one of the women what her most important piece of advice to a younger woman would be. She replied simply “Have a dream. It doesn’t matter what it is, but you have to have a dream.”

After these women had chased and caught one dream, they kept on. Following the W.A.S.P. program, Jacqueline Cochran became the first woman to break the sound barrier, the first woman to take off from an aircraft carrier, and the first woman to reach Mach 2. Other women went on to travel, teach, silversmith, write, and become nationally renowned sculptors. One was even a Rockette who could still lift her leg above her head at the spry age of 92.

This Women’s History Month, I encourage you to read about them if you haven’t before. They accomplished remarkable feats in the face of seemingly untenable odds. If you love flying, you will love the borderline unbelievable stories (I heard several after cocktails and had some doubts, but later fact-checked and found that these ladies had no need to exaggerate). If you love history, you will love what this scrappy group of women from all different walks of life was able to contribute to our country’s success in World War II and to the female pilots who would follow.

I will always love the stories and memories I got to share with the W.A.S.P. I have a small statue of a trainee that displays their motto:

“We live in the wind and sand, and our eyes are on the stars.”

It’s a beautiful reminder of the lessons of wild optimism, humility, and dogged determination they taught me.

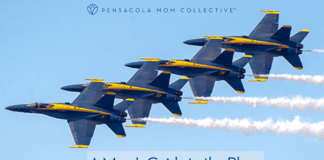

Now that I have a daughter of my own, I am so grateful to these women that when we’re lucky enough to catch the Blues flying over Pensacola, I can tell her a female has flown the biggest plane.

Honey this is an amazing article. Thank you for what you are doing

Brenda Harris